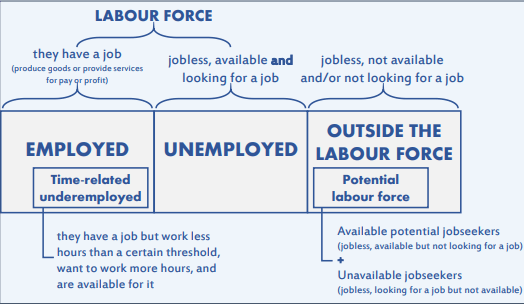

We can classify people of working age according to their labour force status into 3 groups:

the employed,

the unemployed , and

persons outside the labour force.

The employed and the unemployed together make up the labour force. It is the supply of labour available in an economy for the production of goods and services. Thus, people who are neither employed nor unemployed (outside the labour force) are not part of the labour supply. At least not in principle.

Traditionally, people in the labour force support those outside the labour force, often seen as dependents. Therefore, people’s participation in the labour force is key for economic growth and development.

Global labour force participation

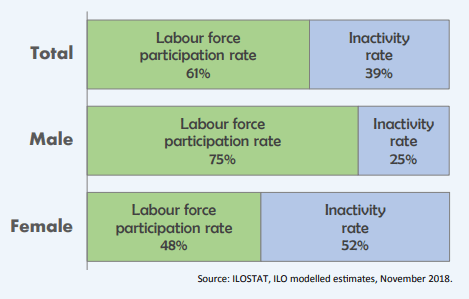

In 2018, 39% of the world’s working-age population was outside the labour force. That is, over a third of all working-age people in the world were not part of the labour supply.

What is more, over half of the world’s working-age women were not in the labour force (52%). Only a fourth of the world’s working-age men were not in the labour force (25%). This reflects a strong gender pattern in labour force participation linked to societal gender roles.

World’s labour force participation rate and inactivity rate by sex (2018)

Shifting world demographics

The world’s population is ageing, and it is doing so faster than ever before. Rising life expectancy and declining fertility rates lead to an increase of the population’s median age. Although the ageing population trend started in high-income countries, it is now affecting most countries. This demographic shift brings major challenges to economies and societies around the world.

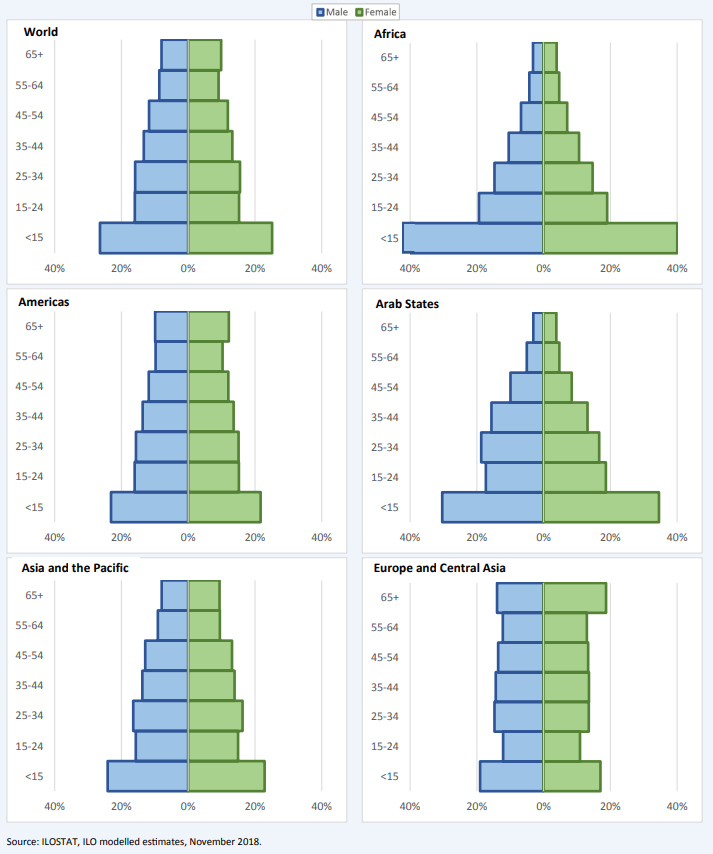

Age distribution of the population by sex and region (2018)

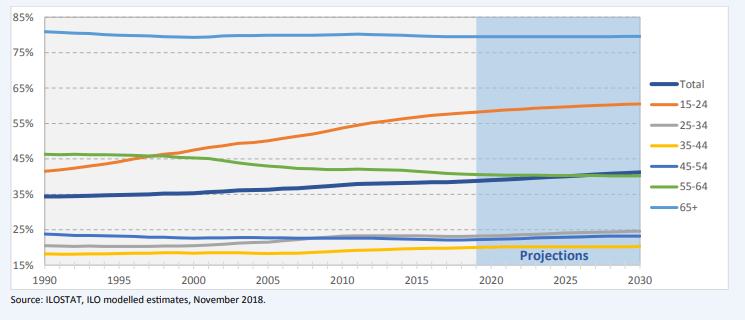

Trends by age

Inactivity trends by age show the impact of demographic and social changes such as the increase in schooling years. In fact, youth’s inactivity rate is rising. This is at least partly because youth are staying longer in education before joining the labour force.

Unsurprisingly, people above 64 have a higher inactivity rate than any other age group by a large margin. The inactivity rate of people aged 55 to 64, however, is on a downward trend. That is, they participate more and more in the labour force, perhaps linked to an increase in the age of retirement.

Evolution of the world’s inactivity rates by age (1990-2030)

Just as the world’s population is ageing, so is its labour force. The median person in the labour force was 33.8 years old in 1990, and 38.8 in 2018.

The ageing of the world’s population and the rise in inactivity rates pose challenges to economic and social systems. We need to address these challenges to ensure communities a sustainable future. However, the inactivity rate is a very gross measure. It is unable to convey the ties that some people outside the labour force still hold to it. In other words, the inactivity rate leads us to believe (mainly through its name) that all persons outside the labour force are inactive, without any interest in or attachment to the labour market. This is far from always being the case.

People outside the labour force may still be attached to the labour market

It is wrong to assume that all persons outside the labour force are inactive. They may well be involved in productive activities not linked to the labour force. For instance, they may participate in volunteer work, unpaid trainee work or own-use production work.

It is also wrong to assume that all persons outside the labour force have no interest in joining the labour force, and keep no ties whatsoever to the labour force.

Indeed, among all persons outside the labour force, some belong to the potential labour force through their attachment to the labour market despite not being in the labour force.

The potential labour force is made up of 2 groups of people not in employment:

- the available potential jobseekers (available but not seeking), and

- the unavailable jobseekers (not available but seeking).

In 2018, 6% of people outside the labour force in the world belonged to the potential labour force.

Regional patterns

Africa has the highest share of persons outside the labour force in the potential labour force: 11% in 2018. When it comes to countries’ income level, low-income countries have the highest share: almost 13% in 2018.

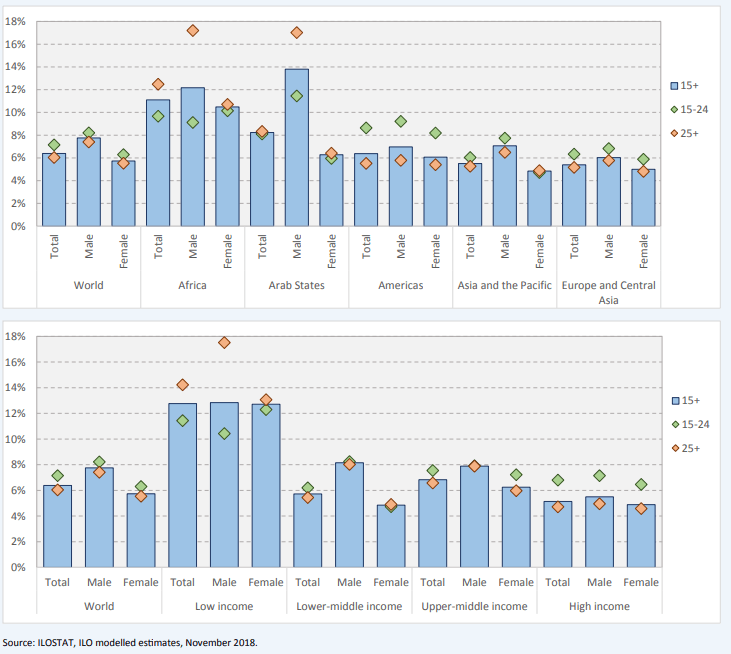

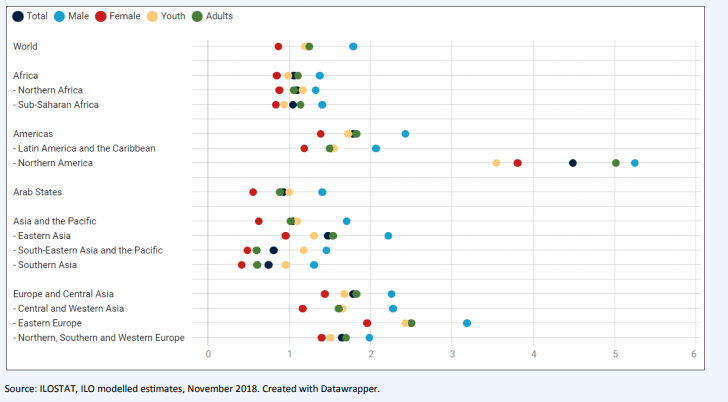

Share of persons outside the labour force who are in the potential labour force by sex and broad age groups (2018)

Gender and age patterns

A big share of people outside the labour force in the potential labour force points to issues of job-search discouragement, inappropriate infrastructure for job searching, insufficient employment office services, and/or hindrances to people becoming available to take up a job (due for instance to inadequate family care services).

In all regions and all income groups, the share of those outside the labour force belonging to the potential labour force was higher for men than for women in 2018.

Regarding age, things are more ambiguous across regions. In Africa and the Arab States, the share of persons outside the labour force in the potential labour force was lower for youth than for adults in 2018. The opposite was true in the other regions.

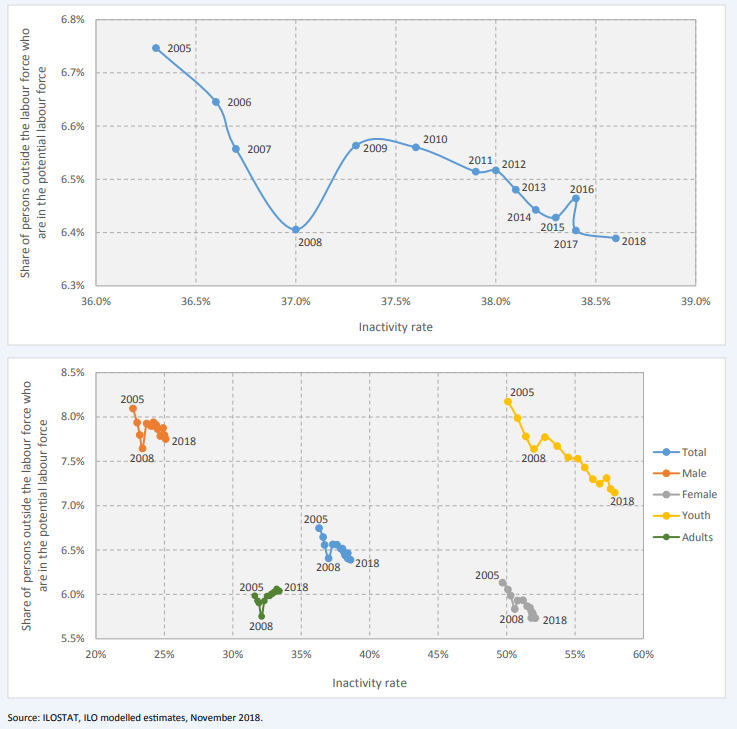

Inactivity rates and the potential labour force

While inactivity rates are growing, the share of persons outside the labour force in the potential labour force is declining. In other words, people participate less and less in the labour force and with weaker ties to it.

Evolution of the inactivity rate and the share of persons outside the labour force who are in the potential labour force by sex and broad age groups (2005-2018)

The ratio of unemployment to the potential labour force

The potential labour force includes people not in employment available but not seeking and those seeking but not available. People not in employment who are seeking and at the same time available are unemployed. The unemployed are part of the labour force since their interest in accessing employment is explicit.

However, it is not always easy to remain unemployed. In other words, it is not always easy to keep job searching and to stay available to take up a job on short notice. Thus, where the job search is difficult and discouraging and where people face obstacles to their availability for employment, the unemployed may quit unemployment and join the potential labour force.

The ratio of unemployment to the potential labour force reflects the hardships of job searching and availability for employment.

A ratio of 1 means that there are as many unemployed as persons in the potential labour force. A ratio of 10 means that the unemployed are 10 times more numerous than the potential labour force. The higher the ratio, the lower the prevalence of job search discouragement, difficulties in job searching and non-availability.

Around the world, perhaps unsurprisingly, unemployment is larger than the potential labour force in almost all regions and sub-regions.

Ratio of unemployment to the potential labour force by region (2018)

Gender patterns

Interestingly, the ratio of unemployment to potential labour force is higher for men than for women. This was true for all regions in 2018. Women face more difficulties to access job search networks and to become available for employment. This, combined with the larger share of persons outside the labour force in the potential labour force for men than for women, implies that men have stronger ties to the labour force than women when they are outside of it, but they are also able to better express their interest in employment explicitly (by looking for a job and being available to start working immediately).

Composition of the potential labour force

The potential labour force includes 2 groups of people, and by focusing on the potential labour force as a whole, we lose key information about labour market deficits. Breaking down the potential labour force into available potential jobseekers and unavailable jobseekers allows us to pinpoint whether people’s difficulties are in job searching, availability for employment, or both. This represents a key insight for policymakers needing to design effective labour market policies.

In 95% of countries with data, over half of the potential labour force are available potential jobseekers (available but not seeking employment).

In 61% of countries with data, 90% or more of the potential labour force are available potential jobseekers.

Simply put, difficulties in job searching are stronger and more widespread than barriers to availability for employment. Jobless people are more often discouraged in their job search than they are unavailable to take up a job.

This is a key finding, proving that it is wrong to assume that the two groups making up the potential labour force have similar significance. Indeed, policymakers should devote increased efforts to address the issue of job search discouragement, which may result from a lack of available jobs, ineffective job search networks, difficulties to access job search infrastructure, or insufficient employment services, among others.

Job search discouragement stronger than lack of availability across the board

There is no strong gender pattern in the breakdown of the potential labour force into its two subcomponents, at least not at the global level. It is clear that in general, the very vast majority of both men and women in the potential labour force are available potential jobseekers.

It is often believed that the issue of not being available to take up a job if an offer comes along affects women more than men given societal roles, which link women more with family care responsibilities. What the data suggest is that, even if this is true, it seems that women unavailable to take up jobs are not looking for jobs either.

Similarly, there are no major differences in the composition of the youth and adult potential labour force. Here too, we could expect youth to be more prone to be looking for a job but not available to start immediately, if they are still studying and they are looking for a job for when they finish. Nonetheless, the data seem to indicate that youth in these circumstances are not looking for a job, or at least not in significant numbers.

Concluding remarks

Demographic shifts are leading to the ageing of the world’s population. This, combined with social, educational and economic changes is resulting in increasing inactivity rates. Increasing inactivity rates can be a cause for concern. However, it is wrong to assume that all persons outside the labour force are inactive or that they keep no ties to the labour market.

Indeed, among persons outside the labour force there are some who belong to the potential labour force:

- the available potential jobseekers, and

- the unavailable jobseekers.

Despite not being in the labour force, they are still putting pressure on the labour market and could potentially join the labour force in the near future.

In some countries around the world, the potential labour force is close in numbers to the unemployed. Where persons in the potential labour force and especially discouraged jobseekers are numerous, policymakers should keep it in mind when designing employment promotion programmes.

Although two different groups of people make up the potential labour force, one of them is much more prominent in most countries: available potential jobseekers. Thus, issues related to job-search discouragement, inappropriate infrastructure for job searching, or insufficient employment office services seem to be more common than hindrances to becoming available to take up a job (or those who face hindrances to availability for employment are not looking for a job).

Therefore, programmes to promote job creation, facilitate the job search process and help potential employers reach potential workers can have a great impact not only on employment rates, but also on labour force participation.

If you are interested in reading more about inactivity and the potential labour force, check out the full brief here.

Author

-

Rosina Gammarano

Rosina is a Senior Labour Statistician in the Statistical Standards and Methods Unit of the ILO Department of Statistics. Passionate about addressing inequality and gender issues and using data to cast light on decent work deficits, she is a recurrent author of the ILOSTAT Blog and the Spotlight on Work Statistics. She has previous experience in the Data Production and Analysis Unit of the ILO Department of Statistics and the UN Resident Coordinator’s team in Mexico.