The Education and Mismatch Indicators (EMI) database includes employment by education, mismatch indicators produced based on level of education, and work-based learning indicators.

Employment by education

Introduction

Human resources are the most valuable and productive resource. Countries depend on the health, strength and skills of their workers to produce goods and services for consumption and trade. The advance of complex organizations and knowledge requirements, as well as the introduction of sophisticated machinery and technology, means that economic growth and improvements in welfare increasingly depend on the degree of literacy and educational attainment of the population. People’s predisposition to acquire such skills can be enhanced by experience, informal and formal education, and training.

Information on the employed population by level of educational attainment provides insights into the human capital dimension of employment with potential implications for both employment and education policy.

ILOSTAT contains statistics from national sources on employment by level of educational attainment, also disaggregated by sex and age. Statistics are available using both aggregate and detailed categories of educational attainment.

Concepts and definitions

Employment comprises all persons of working age who during a specified brief period, such as one week or one day, were in the following categories: a) paid employment (whether at work or with a job but not at work); or b) self-employment (whether at work or with an enterprise but not at work).1Resolution concerning statistics of work, employment and labour underutilization, adopted by the 19th International Conference of Labour Statisticians, Geneva, October 2013

The working-age population is the population above the legal working age, but for statistical purposes it comprises all persons above a specified minimum age threshold for which an inquiry on economic activity is made. To favour international comparability, the working-age population is often defined as all persons aged 15 and older, but this may vary from country to country based on national laws and practices (some countries also use an upper age limit).

Data presented by level of education is based on the International Standard Classification of Education (ISCED). The ISCED was designed by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) in the early 1970s to serve as an instrument suitable for assembling, compiling and presenting comparable indicators and statistics of education, both within countries and internationally. The original version of ISCED (ISCED-76) classified educational programmes by their content along two main axes: levels of education and fields of education. The cross-classification variables were maintained in the revised ISCED-97; however, the rules and criteria for allocating programmes to a level of education were clarified and tightened, and the fields of education were further elaborated. In 2011, a new classification ISCED 2011 was introduced; however, reporting according to ISCED-11 did not start until 2014.2For further details on ISCED 2011, see UNESCO: International Standard Classification of Education/ISCED 2011 (Paris, 2012)

Statistics on employment by level of educational attainment are presented in ILOSTAT according to both the categories of the latest version of the ISCED available and aggregate categories, based on the following correspondence table:

| Aggregate level of education | ISCED-11 | ISCED-97 |

|---|---|---|

| Less than basic | X. No schooling | X. No schooling |

| 0. Early childhood education | 0. Pre-primary education | |

| Basic | 1. Primary education | 1. Primary education or first stage of basic education |

| 2. Lower secondary education | 2. Lower secondary or second stage of basic education | |

| Intermediate | 3. Upper secondary education | 3. Upper secondary education |

| 4. Post-secondary non-tertiary education | 4. Post-secondary non-tertiary education | |

| Advanced | 5. Short-cycle tertiary education | 5. First stage of tertiary education (not leading directly to an advanced research qualification) |

| 6. Bachelor’s or equivalent level | ||

| 7. Master’s or equivalent level | ||

| 8. Doctoral or equivalent level | 6. Second stage of tertiary education (leading to an advanced research qualification) | |

| Level not stated | 9. Not elsewhere classified | ?. Level not stated |

Data sources

Labour force surveys are the preferred source of statistics on employment by educational attainment, since they provide information on both the labour market situation of individuals and their level of educational attainment. Such surveys can be designed to cover virtually the entire non- institutional population of a given country, all branches of economic activity, all sectors of the economy and all categories of workers, including the self-employed, contributing family workers, casual workers and multiple jobholders. In addition, such surveys generally provide an opportunity for the simultaneous measurement of the employed, the unemployed and persons outside the labour force (and thus, the working-age population) in a coherent framework.

Other types of household surveys and population censuses could also be used as sources of data on employment by educational attainment. The information obtained from such sources may however be less reliable since they do not typically allow for detailed probing on the labour market activities of the respondents.

In cases where ILO experts process the household survey microdata in order to produce the indicators published on ILOSTAT, international statistical standards are strictly applied to ensure comparability across countries. Thus, ILOSTAT data may differ from what is nationally reported. The magnitude of the differences depends on the extent to which a country is applying international statistical standards.

Interpretation and uses

Continual economic and technological change means that the bulk of human capital is now acquired not only through initial education and training, but increasingly through adult education and enterprise or individual worker training, within the perspective of lifelong learning and career management. Unfortunately, quantitative data on lifelong learning, and indicators that monitor developments in the acquisition of knowledge and skills beyond formal education, are sparse. Statistics on levels of educational attainment, therefore, remain the best available indicators of labour force skill levels. These are important determinants of a country’s capacity to compete successfully and sustainably in world markets and to make efficient use of rapid technological advances. They also affect the employability of workers.

Examining education levels in relation to employment is also useful for policy formulation, as well as for a wide range of economic, social and labour market analyses. Statistics on levels and trends in educational attainment of the employed can: (a) provide an indication of the capacity of countries to achieve important social and economic goals; (b) give insights into the broad skill structure of the employed population; (c) highlight the need to promote investments in education for different population groups; (d) support analysis of the influence of skill levels on economic outcomes and the success of different policies in raising the educational level of the workforce; (e) give an indication of the degree of inequality in the distribution of educational resources between groups of the population, particularly between men and women, and within and between countries; and (f) provide an indication of the skills of the existing employed population, with a view to discovering untapped potential.

Limitations

A number of factors can limit the comparability of statistics on employment by level of educational attainment between countries or over time. Comparability of employment statistics across countries is affected most significantly by variations in the definitions used for the employment figures. Differences result from age coverage, such as the lower and upper bounds for labour force activity. Estimates of employment are also likely to vary according to whether members of the armed forces are included. Another area with scope for measurement differences has to do with the national treatment of particular groups of workers. The international definition of employment calls for inclusion of all persons who worked for at least one hour during the reference period.3The application of the one-hour limit for classification of employment in the international labour force framework is not without its detractors. The main argument is that classifying persons who engaged in economic activity for only one hour a week as employed, alongside persons working 50 hours per week, leads to a gross overestimation of labour utility. Readers who are interested to find out more on the topic of measuring labour underutilization may refer to ILO: “Beyond unemployment: Measurement of other forms of labour underutilization“, Room Document 13, 18th International Conference of Labour Statisticians, Working group on Labour underutilization, Geneva, 24 November – 5 December 2008

Workers could be in paid employment or in self-employment, including in less obvious forms of work, some of which are dealt with in detail in the resolution adopted by the 19th ICLS, such as unpaid family work, apprenticeship or non-market production. Some countries measure persons employed in paid employment only and some countries measure “all persons engaged”, meaning paid employees plus working proprietors who receive some remuneration based on corporate shares. Other possible variations to the norms pertaining to measurement of total employment include hours limits (beyond one hour) placed on contributing family members before for inclusion in employment.4Such exceptions are noted in the footnotes and/or metadata fields in ILOSTAT’s data tables. The higher minimum hours used for contributing family workers is in keeping with an older international standard adopted by the International Conference of Labour Statisticians in 1954. According to the 1954 ICLS, contributing family workers were required to have worked at least one-third of normal working hours to be classified as employed. The special treatment was abandoned at the 1982 ICLS.

Comparisons can also be problematic when the frequency of data collection varies widely. The range of information collection can run from one month to 12 months in a year. Given the fact that seasonality of various kinds is undoubtedly present in all countries, employment figures can vary for this reason.

The way in which employed individuals are assigned to educational levels can also severely inhibit cross-country comparisons. Many countries have difficulty establishing links between their national educational classification and ISCED, especially with respect to technical or professional training programmes, short-term programmes and adult-oriented programmes (ranging around levels 3, 4 and 5 of ISCED-97 and ISCED-11). In numerous situations, ISCED classifications are not strictly adhered to; a country may choose to group together some ISCED categories. It is necessary to pay close attention to the notes in order to ascertain the actual distribution of education levels before making comparisons.

An issue that affects several countries in the European Union originates from the way in which those who have received their highest level of education in apprenticeship systems are classified. The classification of apprenticeship in the “secondary” level – despite the fact that this involves one or more years of study and training beyond the conventional length of secondary schooling in other countries – can lower the reported proportion of the labour force or population with tertiary education, compared with countries where the vocational training is organized differently. This classification issue substantially reduces the levels of tertiary education reported by Austria and Germany, for instance, where the participation of young people in the apprenticeship system is widespread.

There is also the potential for further confusion as to how a person’s educational level is to be defined. Ideally, when making cross-country comparisons, all data should refer to the highest level of education completed, rather than the level in which the person is currently enrolled, or the level begun, but not successfully completed. However, because data are usually derived from household surveys, the actual definition used will inevitably depend on each respondent’s own interpretation.

Mismatch by level of education

Introduction

A person in employment may experience different forms of mismatches such as mismatch by level of educating, mismatch by field of study and /or skills mismatch. Any forma of mismatch can have significant impact on individuals’ labour market outcome. If widespread and persistent, it can result in high economic and social costs for workers, employers and society.

Statistics on various forms of mismatches (both incidence and trends) are in great demand for use by policy departments, educational institutions and businesses. Reliable internationally harmonized statistics on the qualifications (both formal and informal) and skills possessed and used by workers provide a better understanding of their impact on labour market outcomes and ensure that effective policy measures and tools are formulated to improve the quality and relevance of skills formation.

Concepts and definitions

Qualification mismatch refers to a situation in which a person in employment, during the reference period, occupied a job whose qualification requirements did not correspond to the level and/or type of qualification they possessed. Qualification mismatch includes:

- Mismatch by level of education: it occurs when the level of education of the person in employment does not correspond to the level of education required to perform their job.

- Mismatch by field of study: it occurs when the field of study of the person in employment does not correspond to the field of study required to perform their job.

Educational attainment is the highest level of education an individual has successfully completed. This is usually measured with respect to the highest education programme successfully completed, which is typically certified by a recognized qualification.

Field of study is the broad domain, branch or area of content covered by an education programme, course or module.

Qualification is the official confirmation, usually in the form of a document, obtained through:

- successful completion of a full education programme;

- successful completion of a stage of an education programme (intermediate qualifications); or

- validation of acquired knowledge, skills and competencies, independent of participation in an education programme (acquired through non-formal education or informal learning).

Qualification mismatch differs from skill mismatch. Skill mismatch refers to a situation in which a person in employment, during the reference period, occupied a job whose skills requirements did not correspond to the skills they possess.

Skill mismatch includes:

- Mismatch of job-specific/technical skills

- Mismatch of basic skills

- Mismatch of transferable skills

Skills are defined as the innate or learned ability to apply knowledge acquired through experience, study, practice or instruction, and to perform tasks and duties required by a given job. Distinction might be made between:

- Job-specific/technical skills. These are skills particular to an occupation which include specialist knowledge needed to perform job duties; knowledge of particular products or services produced; ability of operating specialized technical tools and machinery; and knowledge of materials worked on or with.

- Basic skills. These skills (such as literacy, numeracy and ICT (Information Communication Technology) skills) are considered as a prerequisite for further education and training and for acquiring transferable and technical skills.

- Transferable skills. These are skills that are relevant to a broad range of jobs and occupations and can be easily transferred from one job to another. They include but are not restricted to problem-solving and other cognitive skills, physical skills, language skills, socio-emotional and personal behavioural skills.

Computation method

Mismatch by level of education and mismatch by field can be estimated by using three approaches: normative, statistical and self-assessment approaches, all of which use information about the highest level of educational attainment of a person in employment, their occupation and the relevance of different levels of education to each occupation or occupational group. The series in this database are based on normative and statistical approaches.

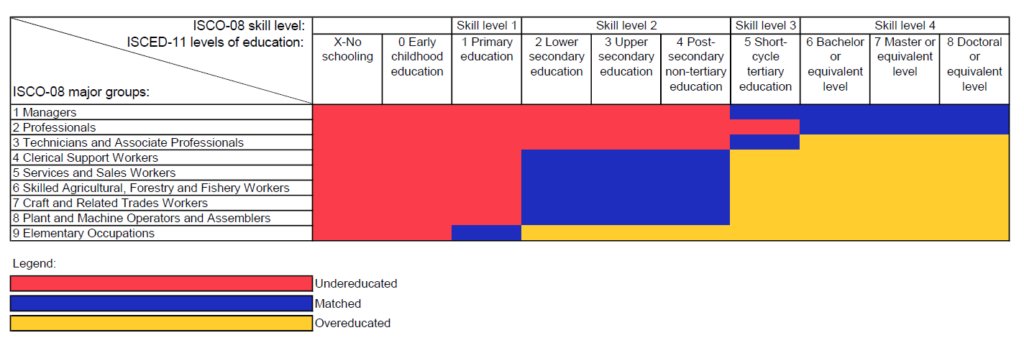

The normative approach used to identify mismatched workers is based on the educational requirements set out in the International Standard Classification of Occupations (ISCO) for each one digit ISCO occupational group, and on the level of education of each person in employment. Each individual is assigned a status based on whether their level of education corresponds to the educational requirements for their particular occupational group. This method yields a proportion of workers who can be classified as:

- matched (individuals whose highest level of education corresponds to the ISCO educational requirements for their occupation)

- overeducated (individuals whose highest level of education is above the ISCO educational requirements for their occupation)

- undereducated (individuals whose highest level of education is below the ISCO educational requirements for their occupation)

The statistical approach involves comparing the educational attainment of those in employment with the average level of educational attainment for their occupation (average based on all workers in an occupation), using two digit ISCO occupational groups. Each individual is assigned a status depending on whether their level of education corresponds to the average for their occupation. The most common educational level for workers in each two-digit ISCO group (that is, the mode) is used as an average.

Correspondence table between education and occupation based on ISCO-08 educational requirements

It should be noted that in addition to mismatch by level of education, workers can experience other forms of mismatch such as field of study mismatch and skill mismatch. The level of educational attainment is only an approximation of the skills, knowledge and competencies possessed by an individual at the time of completion of an educational programme. It does not reflect the fact that skills and knowledge may become obsolete over time or that workers may acquire new skills outside formal education (through on-the job training, experience, self-learning, social activities or volunteering). As a result, two persons with the same level of education may have very different sets of skills. Skill mismatch can be estimated based on workers’ and employers’ assessment of skills possessed and required or through direct assessment of skills possessed. However, these data do not exist in this database or other ILOSTAT databases.

Data sources

Data on mismatch by level of education, which are published in this database, are based on data collected through labour force survey or other household surveys which include information on the highest level of educational attainment and occupation of employed household members.

The measurement of qualification and skill mismatches, which are not published in this database, should be based on suitable data compiled as part of the existing household and/or establishment based surveys. Data from recent administrative records and secondary sources can also be used.

Interpretation and uses

Although qualification is an approximation of skills, the knowledge and competencies mastered at the time of completion of educational programmes provide only a very rough indicator of current skills because they may either (a) become obsolete over time if not used, or (b) increase as workers acquire new skills outside formal education through on-the-job training, experience, self-learning, social activities or volunteering etc. In addition, qualifications do not indicate an individual’s ability: two persons with the same qualification may have very different abilities. Hence the need to separately measure qualification and skills mismatches.

In order to support evidence-based policy-making to reduce mismatch, there is a need to:

- assess the extent to which the qualifications and skills of persons in employment correspond to the type and level of skills required by their jobs;

- identify qualification and skill deficits resulting from ongoing technical, structural and demographic changes in the economy;

- identify qualification and skill surpluses and workers whose skills and qualifications exceed those required by the job; and

- identify the causes and consequences of both overskilling and underskilling.

Statistics on the types, levels and trends of qualification and skill mismatches can provide measures of the extent to which the human resources of persons in employment are actually utilized or not. Such information is essential for macroeconomic and human resources development planning and policy formulation.

Work-based learning

Introduction

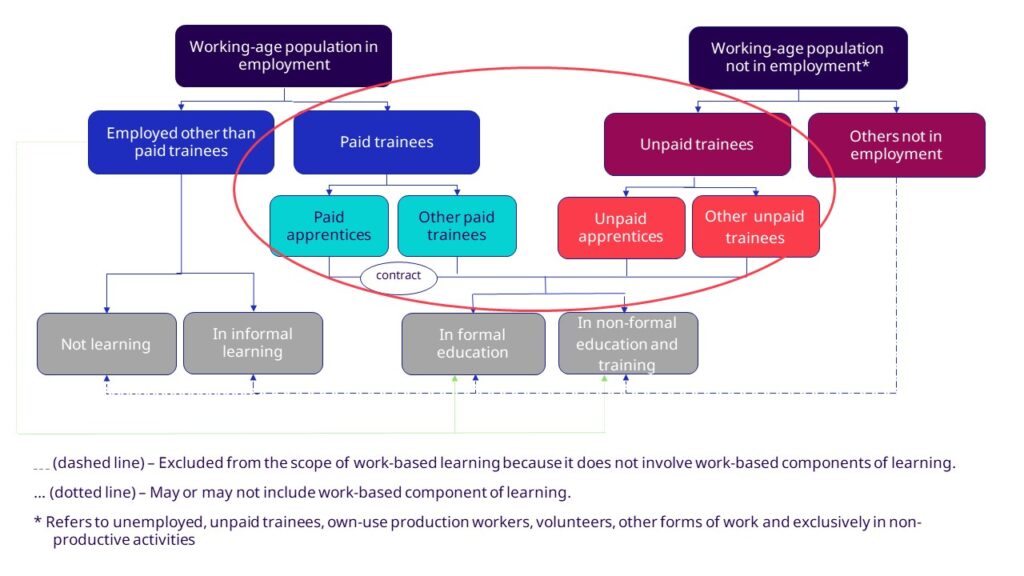

Work-based learning (WBL) is complex and multifaceted. WBL refers to all forms of learning that take place in a real work environment. It may – but does not always – combine elements of learning in the workplace with off-the-job learning. WBL can take place within formal and non-formal education and training as well as informal learning that can be undertaken throughout a person’s lifetime with the aim of improving competences including knowledge, skills and behaviours needed to successfully obtain and keep jobs and progress within individual career pathways. Apprenticeships, internships, traineeships, and on-the-job training are the most common types of WBL. They can be paid on unpaid.

ILOSTAT contains statistics from representative national sources on work-based learners, paid and unpaid, disaggregated by sex and age. Wherever the information is available, statistics on apprentices and other trainees is presented.

Work-based learners that participate in informal learning but also employed that participate in informal education and learning (e.g., attending short courses, workshops, or seminars), are not included in the statistics presented.

Concepts and definitions

WBL refers to all forms of learning that take place in a real work environment. It can provide individuals with the skills needed to successfully obtain and keep jobs, and progress in their professional development. It may – but does not always – combine elements of learning in the workplace with off-the-job learning.

Persons in paid trainee work are defined as all those of working age who, during a short reference period, performed any activity to produce goods or provide services for others, to acquire workplace experience or skills in a trade or profession and receive payment in return for work performed. 5Defined in the International Classification of Status in Employment (ICSE-18) adopted by the 20th ICLS in 2018 (ILO, 2018).

Persons in unpaid trainee work are defined as all those of working age who, during a short reference period, performed any activity to produce goods or provide services for others, to acquire workplace experience or skills in a trade or profession and do not receive any remuneration. 6Defined in the Resolution concerning statistics of work, employment and labour underutilization adopted by the 19th ICLS in 2013 (ILO, 2013).

Apprenticeship refers to structured work-based training usually provided over a longer period that enable the learner to acquire all the competences required to practice a particular trade or occupation. Substantial parts of the training take place within the premises of an employer in real work environments.

Other trainees include traineeships, internships, learnerships and placements. It refers to work-based learning experience that is usually shorter in duration and enable the learner to gain general experience in a type of work or offering an opportunity to practice skills already acquired.

Conceptual framework for statistics on work-based learning

Data sources

Country-level data are based on national labour force and other household surveys in the ILO Harmonized Microdata Collection.

Details regarding country practices are available in the paper National practices in measuring work-based learning: a critical review.

Interpretation and uses

Statistics on the types, levels and trends of work-based learning can provide measures of the extent to which youth and adults participate in work- based learning. Such information could support the formulation, monitoring and evaluation of specific laws, collective agreements, policies and programmes for vocational education and training, skills development, and reskilling of workers.

Statistics on levels and trends in WBL can: (a) provide an indication of the capacity of countries to achieve important social and economic goals and facilitate school to work transition; (a) highlight the need to promote work-based learning for different population groups, including mean and women, youth and adults, the vulnerable ones; particularly between men and women, youth and adults, persons with disabilities and other vulnerable groups, (c) provide an indication of the quality of work based learning, (d) promote the availability and access to quality apprenticeship.

Limitations

The WBL data presented on ILOSTAT cover only participation in work-based training that is part of formal education or non-formal education and training. Other forms of WBL such as participation in informal learning, and non-formal learning of employed (e.g., attending short courses, workshops or seminars) are not covered.

The data on “apprenticeship” and “other trainees” as nor fully comparable across countries, as they mean different things in different countries. In many countries the boundaries are blurred. Also, there is a significant variation across countries in identifying apprentices and other work-based trainees – depending on the country, they may be identified among the employed, unemployed or outside the labour force. Some countries only ask relevant work-based learning questions only to those currently in employment, while others could identify work-based learners also among those unemployed or outside the labour force.

Note: Many publications are available only in English. If available in other languages, a new page will open displaying the options on the right.