The level of education required in a job does not always match workers’ level of education. Oftentimes workers are either over-educated or under-educated for their jobs.

ILOSTAT now has data on the mismatch between workers’ level of education and the expected level of education for each job (based on the job’s occupational group) for 114 countries from all regions and income levels. In 46% of those countries, over half of all workers have jobs that don’t match their educational level.

These are not global estimates, but figures covering the 114 countries with data (which represented 56% of global employment in 2018), meaning that the actual number of under- and over-educated workers in the world is probably much higher.

This means that mismatch by educational level is a big issue, and it is widespread.

Under-education is more common and more serious in low-income countries than elsewhere, while over-education is more prevalent in high-income countries. The ten countries with the highest share of workers in mismatch by educational level are all either low income or lower-middle income.

Ten countries with the largest share of workers in mismatch by educational level

Under-education and over-education coexist

In all countries there are workers who are under-educated and workers who are over-educated for the jobs they hold. However, in the majority (74%) of countries with data, the share of under-educated workers is higher than that of over-educated workers.

What is more, under-education is clearly an issue in developing countries (although not exclusively). In all the low-income countries with data, under-education is more prevalent than over-education. However, this is true in only half of high-income countries with data.

Share of under- and over-educated workers by income group

Both women and men face difficulties matching their education to jobs

The difficulty of finding a job matching one’s educational level concerns both women and men. There doesn’t seem to be a strong gender bias in workers’ mismatch by educational level globally.

Nonetheless, in low-income countries, mismatch by educational level does affect women more than men. Indeed, in all low-income countries with data but one (Rwanda), the share of workers in mismatch by educational level is larger for women than for men.

Share of employed women and employed men in mismatch by educational level

Key takeaways

In short, in low-income countries, employment is concentrated in low-skilled occupations requiring a lesser level of education and workers are more likely to be under-educated for their jobs. Conversely, in high-income countries, employment is concentrated more in occupations requiring higher skill levels, and workers’ under-education is less common.

Actually, in high-income countries almost all workers in low-skilled jobs are over-educated.

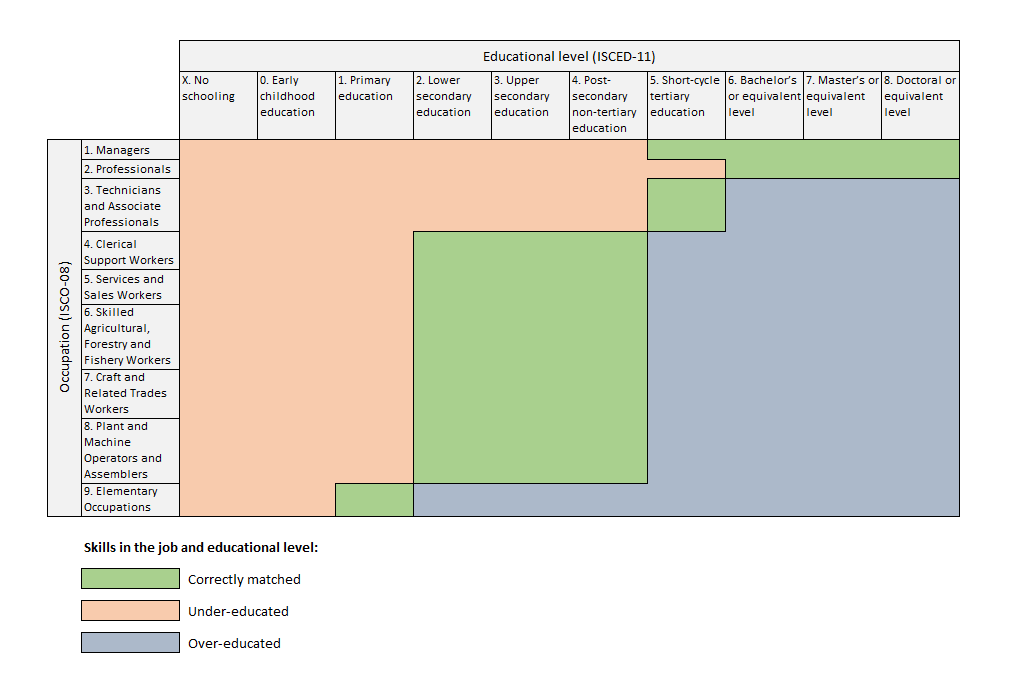

Our method

Naturally, in order to define who is mismatched and who isn’t, we had to establish some criteria. Using the International Standard Classification of Education and the International Standard Classification of Occupations, we determined the expected level of education of workers in each occupation for them to be well matched for the requirements of the occupation. Anything less than that, and the worker would be under-educated for the job. Anything more than that, and the worker would be over-educated for the job.

Correspondence table between education and occupation

What does this mean for mismatch by educational level in each occupation?

Normative and statistical methods for defining educational mismatch

This article uses data produced by our microdata team. To know more about their amazing work, click here.

See also

The educational level of the world’s labour force is increasing, but it is not always easy for highly educated workers to find jobs matching their expectations. This new Spotlight on Work Statistics explores the advantages and disadvantages of having a tertiary degree in the labour market.

Author

-

Rosina Gammarano

Rosina is a Senior Labour Statistician in the Statistical Standards and Methods Unit of the ILO Department of Statistics. Passionate about addressing inequality and gender issues and using data to cast light on decent work deficits, she is a recurrent author of the ILOSTAT Blog and the Spotlight on Work Statistics. She has previous experience in the Data Production and Analysis Unit of the ILO Department of Statistics and the UN Resident Coordinator’s team in Mexico.

View all posts